Here we are again, just about to set off from Puerto Natales in Chile to make our way to El Calafate in Argentina, the glacier capital, where we will be carrying out expedition work in the Parco Nacional Los Glaciares.

The next morning we go straight to the park headquarters to complete the lengthy paperwork and finalize the logistics of getting to the glaciers. Given our shared objectives, the park authorities kindly confirm their backing and invite us to take advantage of their vehicles and park rangers, who are willing to lend us a hand in the field, which is essential as the places we are heading for are in the remotest and most protected areas of the park.

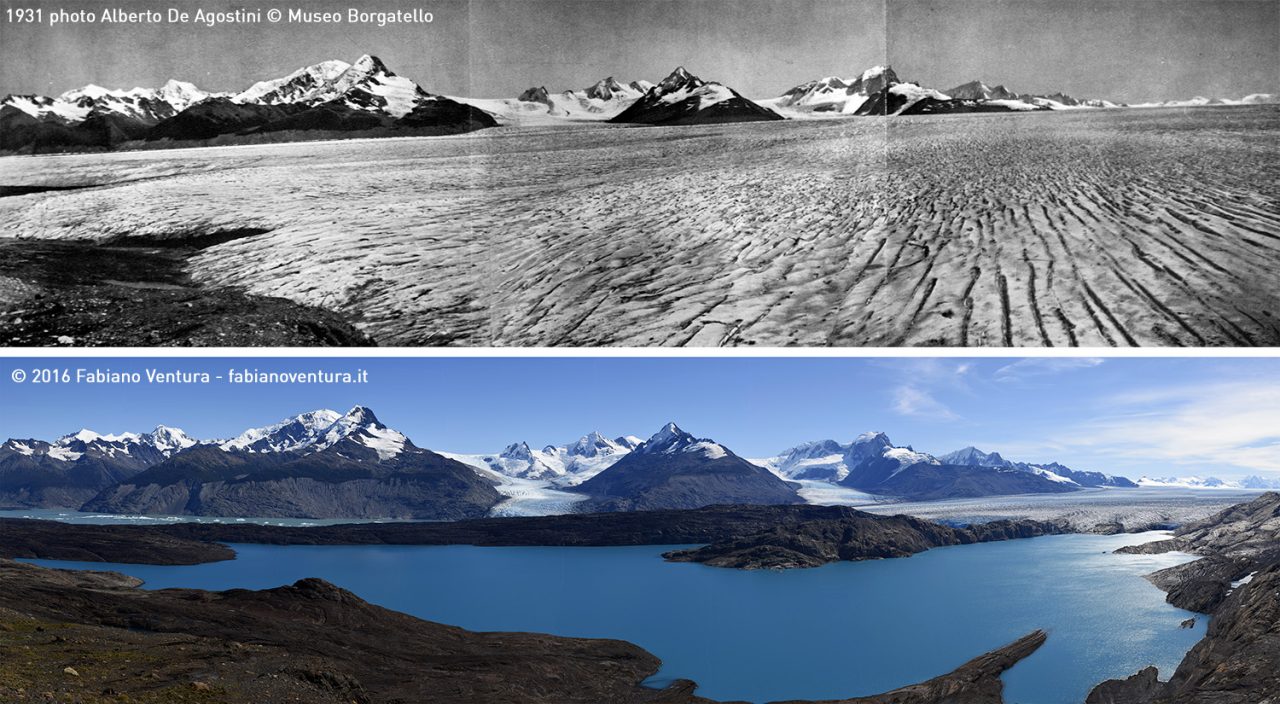

Once we agree on an outline schedule, subject of course to prevailing weather conditions, we come down in favour of the Upsala Glacier, Argentina’s second largest glacier, as our first location. After crossing the Argentino Lake by tourist boat we reach the long-standing Argentinian Glaciological Institute’s refuge and deposit all our equipment. This leaves us free to go immediately in search of the exact point where De Agostini shot a sequence of seven photographic plates in order to piece together one of his most striking panoramic shots. The sight of the glacier simply takes our breath away. The valley is 60km long and 5km wide, and the trim line, i.e. the signs of erosion on either side of the valley left by the glacier in the Little Ice Age, is clearly visible and reaches over 500 metres in some points. After climbing up several hundred metres over loose rock and scree I manage find the exact spot where De Agostini stood and photographed the panorama from a peak to the left of the viewing platform, confirmed as usual by recognising boulders and rocks captured on archive photos. The view from that point is just stunning, and seeing how such an extensive valley (60km long and 5km wide) has lost so much of the glacial ice mass over 80 years is disheartening.

As the day was coming to an end and night about to draw in it was obvious that I would have to come back the next day.

Unfortunately, once back on the peak the next day, the wind was gale force and I could not even manage to mount my tripod, so I took refuge from the blasts of wind in a small valley lower down from the peak and began to wait for the weather to improve to take the shot. As bad luck would have it, the blasts just got stronger in the early afternoon and I lost hope, and was forced to make my way back to the refuge in order to try again the following day. Before making the descent I left my photographic back pack with the heaviest equipment in the gap between two boulders and took a GPS reading that would enable me to retrace my journey by jeep and boat before making my way back to the refuge and something to eat.

I woke up the next day to good weather and light winds and so made my way to the peak for the third time and wait for the appropriate time (about 3pm) to start taking the shots.

Once back in El Calafate we lost no time in getting ready for the new mission to the Ameghino glacier and the next morning we left with four park rangers in a jeep towing a dinghy. When we got to the Perito Moreno glacier, our intended point of departure, we heard a thunderous sound and realized immediately that the ice retaining wall damming the lake had burst, which made us decide to stay and photograph the spectacle of disintegrating ice. The next day we knew we had to move on and, reluctantly, made the decision not to photograph the final collapse of the mass of ice and so made our way to the Ameghino glacier. Once under the mountain peak we continued our ascent along the crest to avoid the dense vegetation as far as possible, reaching the peak after a strenuous three hour trek through pristine and unchartered territory.

I set to work setting up my tripod, which I anchored to the outcrop with large rocks to hold it steady despite being battered by gusts of wind. I then shot the same sequence of photos as the archive image of the panorama I had taken with me. Once again I noticed considerable ice shrinkage, and where there was once a winding white tongue of ice there was a rock-strewn valley ending four kilometres downstream in lake four kilometres in length that reaches the present glacial front.

The favourable weather conditions persisted but the time left was quickly slipping away, which meant I had to move on to carry out more repeat photography in the El Chalten area of the well-known Fitz Roy and Cerro Torre mountains.

Considering the number of repeat photographs I needed to take of the Spegazzini glacier as well as the travel time to cross the Argentino Lake, I decide to dedicate at least two days to this new mission. We reached the Spegazzini fjord after a rough crossing in our dinghy, surrounded by waves three meters high and incredibly strong winds, and we set up base camp in sight of the glacier.

On the Trail of the Glaciers Andes 2016 – Dispatch 03 from Fabiano Ventura on Vimeo.

The further reaches of Los Glaciers National Park have always fascinated me because they are so difficult to access. I found this webpage after typing a search for ‘old photos from LGNP’. I remember once seeing some old photos taken I think by Agostini from the top of Cerro Polo which is a far more accessible peak within the park. The old images I remember photos showed Piedras Blancas Glacier in maybe the 1950’s. I’ve been coming to the park for a little over 10 years (I’ve spent over 3 years photographing in LGNP). I’ve watched Piedras Blancas Glacier retreat considerably.